When discussing turn of the century business, most of the talk usually focuses on the accomplishments of men. Seldom and few opportunities existed for most women in those days. Most often than not, an ambitious and career-minded woman would end up on a pathway of frustration and sorrow rather than to feel the upward slant of the ladder of success. ![]() |

| September 1893 ad for Maria Culton's hat shop from the "Carbon Advocate." |

![]() |

This turn of the century photo of downtown Lehighton

is taken from the bottom of South St looking toward

South First Street in the vicinity where Maria Culton

owned property and where Benjamin K. Culton ran

a bakery for about twenty years. Photo is courtesy of

Bill Schwab. |

However, there was one Lehighton area women who was able to buck that trend: The thrice married Maria Horn Nusbaum Guth Culton.

Buried along with one of her daughters and granddaughters along Fourth Street, between the towering obelisks of Brinkman and Beltz, is the lone and tall rectangular memorial to Mrs. Maria Culton. The memorial attests to the wealth she amassed.

If given a second look, most passersby would more than likely assume she either was born into it or married into the money. It was Maria’s intelligence and hard work that allowed her to climb. She was self-propelled. She earned it all on her own.

![]() |

This is Mariah "Mary" (Strauch) Rabenold in the late 1920s or

early 1930s at the corner of South and First Sts Lehighton.

. She was a "milliner" here in Lehighton at

the same time Maria and Belle ran their hat business. |

Her story begins with the marriage of Christian and Catherine (Davis) Horn of “North Whitehall” Township. Shortly after their wedding they lived near Ben Salem Church in Andreas. They baptized four of their children there: George in 1807, Esther in 1814, Hermann in 1816 and Rebeka in 1817. (There is no clear reason for the gap in time between George and Esther.)

According to a 1910 Lehighton Press retelling, Christian Horn was an “influential pioneer in this vicinity.” He was known to be a butcher by trade but was also known to have operated a tavern on Bankway in the 1840s. It was said to be near the end of the wooden covered bridge that spanned the river into Weissport.

![]() |

A copy of Christian Horn's 100-acre land grant application. It is unclear

whether the word written on the second page said the land or payment

was "received" or perhaps "retracted" in March of 1839. He applied

for the land in Lausanne Township in 1834. He was never understood

to have taken up residence there. |

In 1834 Horn applied for a 100-acre land grant in Lausanne Township (up the Lehigh River a small ways from Mauch Chunk). The claim was either settled or withdrawn in 1839.

Later, sometime after July of 1850, his wife Catherine dies. For reasons not known, Christian then relocated to Somerset County where he died in 1859 at the age of 75. (There are two men, known to be possible brothers of Christian, buried in Weissport’s Bunker Hill Cemetery: Abraham Horn (1784-1851) and Jacob Horn (1775-1867).)

Though some of his at least ten offspring appear to have spread themselves far and wide, it appears that five of them stayed in the Lehighton area: Herman, Sarah, Amanda, Eliza and Maria. Herman Horn served in the Civil War and lived his retirement years in Bethlehem. He was appointed for a few short months to 1st Lieutenant of Company A of 4th PA Cavalry.

Sarah Horn (1819 to 1897) was a wife of James Conner (both are buried in Parryville). Amanda married John Arner of the Weissport area who was a carpenter, employee of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company and at one time served Carbon as County Commissioner.![]() |

This picture was taken before Citizen's National Bank was built

in the burned out section of buildings. The Lehighton Hi-Rise

would be out of frame to the right. The Leuckel Building seen here still

has the sign reaching off the roof centered between the finales, but

today it retains the name of a previous owner "White's Trading."

The building to the left of that is 115/119 North First Street. The left

side was the site of Elias Snyder's Drugstore and the basement was

the location of his suicide. The burned out building was last owned by

T. C. Horn Drugs from 1900 until the fire in 1908 or 1909. Previous to Horn

it was owned by A. P. Faucet. |

Eliza Horn (1833-1914) married Elias H. Snyder (1833-1903) who owned one of Lehighton’s first drugstores. He started it as early as 1875. It was located at 119 N. First St. Elias was the “Honorable” E. H. Snyder as he served in the legislature for Carbon County in 1883.

The Lehighton Press was the town paper run by David McCormick (1873-1933) and later by his son Robert (1899-1986) at 131/133 North First St. McCormick employed six men and one woman back in 1903, two of which were under twenty-one years old. The Press ran the following “newslet” in August of 1903 in honor of Eliza and Elias’s forty-third wedding anniversary, containing a bit of irony:

“Both are traveling down the shady side of life and are enjoying good health. Long life to our neighbors.”

![]() |

The graves of David and Bertha McCormick as they

lay in Gnaden Hutten Cemetery in Lehighton. David

and later his son Robert were Lehighton's sole

journalists from the 1890s up until around 1949. |

![]() |

The green double-door building was Elias Snyder's drugstore from 1875 until 1903. The real estate became part of Maria Culton's estate sometime after that. Elias was Maria's sister Eliza's husband. You can compare this modern

Lehighton view with the century old picture above. The brown and white building, the former Rea and Derrick and later Putty White's Trading in the 1980s and 1990s was originally built by father and son Frederick and John Leuckel. Both men died in 1899 from separate illnesses. You can see the a picture of that building in Post Two of downtown Lehighton businesses by clicking here. |

But Elias did not live a “long life” after this printed.

Maria was the youngest. Her mother died in the summer of 1850 and given that her father left the area shortly after that might have impelled Maria to marry at the early age of fifteen.

Maria’s first husband was Charles Nusbaum. He was born in Germany and in 1860 was working as a “brewer.”

(There were two beer bottlers in the area by the 1890s. One of them, Fred Horlacher's bottling works were at Bankway and Bridge Streets. Horlacher Beer lived on for several decades in Allentown.)

Besides young Charles, they also had a young women by the name of Susanna Hoffman (age 18) and a woman named Caherine Oberle (age 25) living with them. Oberle was also born in Germany.

Charles and Maria had three children together: Charles H.(1857-1917), Emma C. (1860-1922), and Belle (1862-1926). Charles H. Nusbaum was known as “one of Weissport’s best known businessmen.” His 1917 death certificate states he was in the ice cream confectionery business but also an ice dealer. ![]() |

Maria's daughter Belle Nusbaum

had her own millinery shop on

"Bank" (First) Street as this

ad proclaims from May 1886

"Carbon Advocate" paper, which

was printed in Lehighton. |

Mrs. Belle Nusbaum Meredith, herself a strong business sensed woman like her mother, ironically too became widowed at an early age. And daughter Emma C. Nusbaum, married Oliver A. Clauss of Lehighton.

Nusbaum’s death on June 13, 1862 left Maria alone for a time. Perhaps it was during the war, with so many men away caught up in the fight, which gave Maria the time to establish herself as an independent woman.

Maria’s future husband John Guth had been born in Guthsville. He and his brother Alfred moved to Weissport sometime before the start of the war. It is not known if she knew John before he enlisted, but both John and Maria’s brother Herman Horn served in

![]() |

What John Guth's Company A 4th PA Cavalry

tombstone looked like to ardent Civil War researcher

Joe Nihen of Lansford when this picture was taken

a few years ago. Even though perhaps vandals have

taken this marker, thanks for Nihen's efforts we

still at least have a visual reminder of this man's

service to our country. |

Company A of the 4th PA Cavalry together. Herman was an officer and John was a “farrier” (hoof groomer) and later became the company blacksmith. (Herman resigned only after a few months over his “irritability” of not being named as company commander.)

John’s brother Alfred also fought in the war. He served in Company B of the 176th PA Volunteers. Herman’s short tenure ran from August to December of 1861. John however served nearly the entire length of the Civil War in the 4th Cavalry from August of 1861 until July of 1865.

(There were at least three other Weissport residents who also served in the 4th Cavalry. Joseph and Thomas Connor, a father and son also served. According to Captain William Hyndman from Mauch Chunk and officer in the 4th Cavalry, Thomas was “wild and daring.” ![]() |

Joseph C. Conner served in the 4th Cavalry

along with John Guth. Joseph

served for nearly the whole war mustering out

with his second son Wilford in July of 1865.

Joe continued to fight despite being present

at the loss of his first son Thomas at Kelly's

Ford in the spring of 1863. |

Thomas was shot at Kelly’s Ford Virginia and died at Judiciary Square Hospital in Washington D.C. on May 19, 1863. His father Joseph was said to be on hand when he went down. Joseph continued serving until another son, Wilford reached enlistment age.

Joseph and Wilford would serve out the war together. Joseph returned to Weissport and is buried in Bunker Hill. It is unclear what happened to Wilford after he mustered out in July of 1865. He most likely did not return here. Thomas is most likely buried in a mass grave somewhere near D.C.)

![]() |

Susanna Conner stands quietly amid Bunker Hill's snow.

Often times the grieving mother is a forgotten

part of many Civil War stories. Her mind must

have been terribly worried while both her

husband and eldest son served. She surely had an

even heavier burden of worry after Wilford also signed on. |

So it was that Maria married her second husband John Guth sometime after the summer of 1865. In May 1867 Maria’s fourth and final child was born, daughter Lillian Guth. It is not known if the war negatively impacted John’s health, but John died at the young age of forty, leaving Maria to grieve yet another husband.

It was during her second time of grief as a single woman from September of 1874 until the mid-1880s that saw the rise of Maria’s business empire.

It wasn’t easy. Records show that Maria gave her children over to her sister Eliza and her drug store husband Elias Snyder to help raise them. Though the papers only credit her youngest child Lillian Guth (1868-before 1930) as being their “adoptive” child, the records show the other children were also living with the Snyders for at least part of this time.

With her hat manufacturing business in full swing and her children off and being successful in their own right, Maria certainly was in no urgent need to marry for convenience. There was no reason why Maria couldn’t marry solely for love. And that, according to the press accounts, is exactly what she did.

For husband number three, she chose a man twelve years her junior. Perhaps it was blind love or perhaps she was simply trying to ensure she’d never bury another husband again, but after ten years of marital solitude, Maria united with fellow Lehighton businessperson Benjamin K. Culton (1851-1937).

Surely even if it wasn’t for love, no one would shame Maria for securing such a “trophy husband.” They married sometime around 1885.

The 1900 census record bears witness to Maria’s strong disposition. Rare for this time-period, Maria listed herself as “head” of the household in front of her fairly successful businessman husband B. K. Culton.

![]() |

T. D. Clauss was an early tailor and founding member of the town of

Lehighton. His clothing store was located at 130/132 North First

Street next to Kutz Cigar Store. To the left of this picture is would be the

corner of North Street where the bank is today and Blue Ridge Cable

would be a few doors and across the alley to the right of this photo.

The older gentleman looks to be T. D. Clauss himself. This photo

appears courtesy of Paula Kistler Ewaniuk, T.D.'s great,

great granddaughter. |

Besides burying two husbands of her own, Maria would be called upon to help her grieving sister Eliza. In December of 1902, Elias Snyder, the longtime Lehighton druggist, set upon his normal and methodically mundane morning duties: He tended the fires, fixed a kettle of tea, and saw to the filling of the coal box next to the stove.

Within only a few moments of when witnesses recalled seeing him sweeping the sidewalks in front of his store, he sat himself upon a crate before a mirror at a basement workbench. Taking deliberate aim, he raised the muzzle of his thirty-two caliber pistol to his right temple and put a hole through his head.

It was said that he was upset about a recent kidney issue and he was worried over the slow decline of his business. His behavior was indicative of the popular thinking of the time of having a “clean” death, one in which a person has the time to put his affairs in order. It was the same thinking that placed a death by consumption (tuberculosis) as romantic, virtuous, and noble.

B. K. Culton was an interesting character in Lehighton’s history. He was born in Shamokin to a family of coal miners. He and all his siblings, including allegedly a sister, all worked for the mine company. He came to Lehighton and quickly embedded himself here.

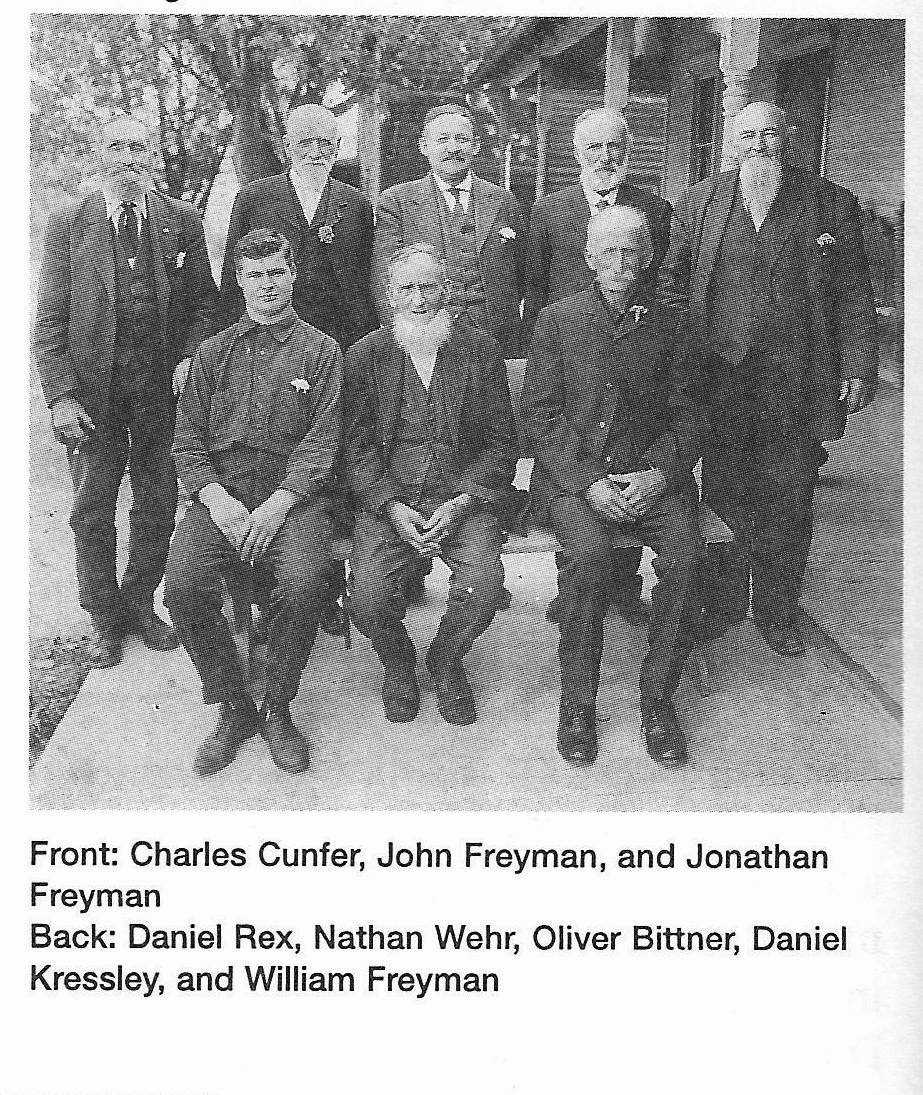

He was a councilman, served on the first board of trustees for the Methodist Episcopal Church on South First St, and was one of the initial members of the Carbon County Historical Society that formed in 1914.

A March 1889 article announced Ben was partnering up with Maria's son, Charles H. Nusbaum. It said that "C. H. Nusbaum" and "B. K. Culton" planned to open a "grocery, confectionery and toy store in connection with an ice cream parlor in the large room in Gabel's block," on First Street. An 1893 ad spoke of selling ice cream at thirty cents a quart and eighty-five cents a gallon.

![]() |

The March 1889 article announcing the partnership between

Maria's son and her new husband Ben Culton. Maria and Ben married

around 1885. |

All told, with her union to Culton, Maria and her family were a formidable force in the Lehighton/Weissport business community. Her widowed daughter Belle Meredith helped Maria manager her shops and business holdings as an equal partner. Her son Charles Nusbaum and his dressmaker wife owned several Weissport stores.

![]() |

Perhaps this is an example of the Culton millinery

handiwork. This is Leila Weiss of Weissport around

1918. She was born in 1893 to John and Jeannette

(Spohn) Weiss. She worked as a telephone

operator in her 20s and later a stenographer in

a real estate firm before marrying her husband Ed

Murley when she was in her 40s. She is buried

in Union Hill Cemetery. Photo appears courtesy

of Paula Ewaniuk. |

Maria’s youngest child, Lillian Guth (1868-after 1930), married Aaron F. Snyder (1858-after 1930). She also ran her own dress shop and millinery. Her husband Aaron had a hand in several businesses, starting out as a furniture maker and an undertaker in the home of what later became the Heller Funeral Home in Weissport. He also sold pianos, organs, and sewing and washing machines.

In the 1890s, Snyder sold “Western” washers with ringers for $7.50, without for $5.00. He sold pianos from $180 to $325 and sewing machines for $25-$35. In one month in 1893 Snyder once claimed to have sold over 600 washing machines. His brother Milton owned and operated “Snyder’s Popular Bazaar” across the canal near the start of Main Road (a parking lot is there now on the right).

![]() |

Here is a scan from Eckhart's "History of Carbon County" of Aaron

Snyder's brother Milton's store on Main Road. Today it is a parking lot

just above the four-way stop. |

Maria’s daughter Emma Nusbaum married Oliver Clauss of Lehighton. Clauss too was the product of Lehighton business, he was the son of Tilghman D. Clauss. T. D.’s tailor shop on First Street employed five people. He was also an early town leader and judge of elections in the 1860s.

T. D.'s father Daniel owned the building at 130/132 North First Street since 1875. T. D. and his wife ran the hotel at Normal Square for five years starting in 1857. After that, he began establishing himself as a tailor on First St. He died in 1901 and his son Frank Clauss took it over the following year and ran it there until 1908.

T. D.'s other son, Oliver Clauss, was a clerk at the court house in 1900 and ten years later he and Emma Nusbaum Clauss moved to Wilkes-Barre where he was a bookkeeper in a brewery. They raised their family there, but they are buried in the Gnaden Hutten cemetery.

![]() |

Oliver was the son of Lehighton tailor T. D. Clauss. Here

are Oliver and Emma's headstones from the Gnaden Hutten

Cemetery. Photos courtesy of Paula Kistler Ewaniuk who

is a great great granddaughter of Tilghman Clauss. |

At least two of Maria’s employees were from Hazleton. Miss Annie Hartig and Leona Celiax. Celiax was the “head trimmer” for years and married Horace Strang of Philadelphia in September 1909.

Maria must have been an affable woman to work for, because on more than one occasion, the newspaper retold accounts of birthdays and ![]() |

Emma Nusbaum Clauss was the youngest daughter of

Maria Horn Nusbaum Guth Culton. Emma and her husband

Oliver lived in Wilkes-Barre for a time after the were

first married. |

anniversaries of Maria’s family, which included the names of some of her employees as guests.

One employee, Miss Elsie Rouse was allowed a leave of absence when she was summoned home to her home in Clayton, New Jersey after her mother died. She had been attempting to start a fire using coal oil when she suffered fatal burns.

At times the lines between employee and family seemed to have been blurred as the 1900 census record indicates. Starting with the employees living with Maria and Ben at their White St., Weissport home were: Carrie Heintzelman, clerk as well as were Effie Brumbaugh, Edith Clark and Leona Celiax, who were all “milliner trimmers” in their early twenties.

The household also included Belle, who was already widowed, and her eleven year old daughter Marguerite (1888-1955). Seventy-three year old Alfred Guth (1826-1907), brother to her second husband also lived there with his forty-three year old, never married daughter Josephine, known as “Phoena” (1856-1936).

Maria’s niece “Phoena” was living there as Maria’s “servant.” Forty-two year old Maria Roth was also live-in servant help. Also boarding there was twenty-two-year-old Ammon Metzger who was a clergyman.

As much good as having a strong feminist role model as they had in their boss, few of Maria’s employees seem to have made a longtime career in the trade after they married. Annie Hartig married Alvin Pohl of Weissport in June of 1897 and Carrie Heintzelman who was at least a ten year employee married Frank Wilson of Mauch Chunk in June of 1900.

When my own grandmother married in Lehighton in September of 1911, she listed her occupation as “milliner.” No one in our family ever heard of her working in the hat trade while married. (She did, however, work at the Baer Silk Mill after she was widowed in 1950.)

![]() |

This is a scan of Mary Strauch Rabenold's September 1911 wedding

application. Her family moved to Allentown sometime before 1910.

Mary was able to support herself for more than a year in the hat-making

trade. |

Benjamin Culton was not immune to tragedy either. In the spring of 1904, he received the sad news of the premature death of his brother back in Shamokin. Then a month later, Ben’s dead brother’s son George, a station agent in Lewisburg, was run over and killed by a train.

Compounding this, a week later someone broke into his nephew’s house and stole $400 cash, of which, $150 was from his father’s death pension. The final insult came in the spring of 1909 when he learned of the death of his 45-year-old brother George.

Also in 1909, Culton was called upon to try to solve the murder mystery of civil war veteran Henry Koch of Lehighton. Koch, who lived across the street from Schafer’s saloon on North Second Street, and who was known to take residence there from time to time as caretaker, was found shot dead there in February of 1909. Culton served on the inquest jury for the case in which no culprit was ever found.

Another First Street business owner was Isborn S. Koch (1850 to c.1930). He started manufacturing “fine Havanan” cigars in Lehighton in 1876.

![]() |

Here is a scan of I. S. Koch's "fine Havana Cigars" in Lehighton. He

operated the manufacture and sales of his cigars from the late 1800s into

the 1920s. |

(According to the town census records, up until about 1920, the preferred spelling of cigar was “segar.”)

Koch employed ten people, eight of whom were men and two were women in 1903. Two employees from the 1890s were Preston Koch and James Yenser. In the early 1900s, two other employees were A.D. Buck and John Rehr. These names were mentioned in Lehighton Press accounts of that time as working there. One man was referred to as employed in “the rolling of the weed at I. S. Koch’s.”

Isborn Koch married Ellen (1857-) and they had two of their three children live to adulthood. Martha (1883-) married South First Street jeweler Harry J. Dotter. Their wedding was by today’s standards unusual in that it was held on a Tuesday at noon. It took place in Koch’s “finely decorated home,” presided over by the family relative Bishop W. F. Heil of Illinois.

Isborn and Ellen’s son Howard worked for his brother-in-law Dotter’s jewelry store as a “watchmaker” in 1920 and listed his occupation as just a “jewelry store clerk” in 1940.

![]() |

This is a photo from a large collection of turn of the century photos of

downtown Lehighton businesses discovered and owned by Brad Haupt.

It could be the jewelry and clock shop of Henry J. Dotter from about 1910

where Howard Koch worked as a "clockmaker." Obviously it is possible

to be any number of Lehighton jewelers as well. |

I. S. Koch was involved in helping to solve a local suicide mystery in an odd occurrence of happenstance. In September of 1900, the body of a man was discovered in the Packerton Yard. It was determined that the man had purchased a bottle of carbolic acid from a drugstore in Mauch Chunk and swallowed the deadly dose in a freight car. The man’s age was estimated at thirty-three years of age and he was buried in the “common ground” of the Lehighton Cemetery.

While talking to customers on a routine business sweep through the lower Lehigh Valley, Koch was able to connect the unidentified man to a missing butcher from Richlandtown near Quakertown. His name was George J. Jones and he had a wife and two children. It was fully expected that his family would reinter his body closer to his home.

It appears that as Maria Culton was putting her own affairs in order too, and in doing so, she once again showed her strong feminist side. It was customary to bequeath inheritance and especially family businesses to the eldest son. Even if there were older sister siblings, the oldest son usually got everything. Not so in Maria’s family.

She bypassed her eldest child, son Charles Nusbaum, having proven himself a rather apt businessperson of his own. Instead Maria chose to trust her younger two daughters with handling her estate.

On February 17, 1910, the awaited inevitability happened when Maria succumbed to a long struggle with stomach cancer.

Among the many residential and business properties in her impressive $70,000 estate were several homes along First Street, including her hat “emporium” located at 123 S. First St. It also included the manufacturing factory located at the end of the bridge in Weissport.

(This factory building would later become the Hofford Mill textile mill and is owned by Tommy McEvilly today. It is unclear how much of that building was used for making hats. However Maria owned the entire located that included a foundry and the onetime power plant built there in the early 1890s.)

She also owned the three-story brick apartment building across the street from Fort Allen and various other properties along Bridge St in Weissport.

![]() |

This could be one of the floods to devastate this area of Weissport in the early winter of 1900 or in the spring of 1901.

Note the three-level brick apartment house on the left that belonged to Culton and the Fort Allen Hotel on the right. Photo appears courtesy of the Brad Haupt collection. |

(One story of lore in Weissport relates that both the Fort Allen Hotel and the aforementioned three-story brick building were competing for the same liquor license. While both buildings were under construction, the first one to be completed would receive the sole license. As the story goes Fort Allen was the winner.)

Maria had been grooming Belle Meredith for a number of years. Belle would seamlessly conduct herself as surely Maria would have do so herself. And probably true to her mother’s own spirit, Belle later changed the name of the shop from “Maria Culton’s” to “Belle Meredith’s Millinery.”

Widowed Benjamin K. Culton received the three-story brick apartment house along with $2,500. She gave $500 to her live-in “servant” niece Josephine “Phoena” Guth, $100 to her granddaughter Marguerite Meredith and up to $2,500 to erect a monument.

The remaining balance of the still sizable estate consisting of other dwellings, the foundry and silk mill properties in Weissport were to stay whole for a period of five years, afterward to be divided equally between the surviving four children (Charles Nusbaum, Belle Nusbaum Meredith, Emma Nusbaum Clauss, and Lillian Guth Snyder).

Her unmarried widowed daughter, Belle moved into one of her mother’s homes at 127 N. First St.

Benjamin Culton would remarry a previously married woman named Emma. They lived at 264 South Second Street and ran his bakery into the 1920s. Ben and Emma lived out their retirement years in the home of Emma’s daughter Mary and her husband Fred Cook at 238 East Paterson Street in Lansford. Fred was a clerk for the coal mine.

Interestingly, old maid Josephine “Phoena” Guth, Maria’s niece, continued in the service of the family as Belle’s household servant at 127 North First St. Phoena did so until Belle’s death in 1926.

But Phoena didn’t have to move. Instead, Belle’s daughter Marguerite Meredith Acker moved in, and Phoena stayed on as her servant. You could say Maria’s family “worked her to death,” but to be fair, it should remain that she worked “until her death.”

![]() |

"Phoena" is buried beside a few of the other Guth's buried in

Weissport's Bunker Hill Cemetery. Among the Guth buried here are

the descendants of the original emigrants from Guthsville of brothers

John and Alfred Guth. John was Maria's second husband. |

And true to the tradition begun by her grandmother Maria, Margurite also listed herself as “head” of the household once she married her husband Mr. George Acker. The Acker’s, along with Phoena, also took in a boarder. He was a young teacher by the name of Milton A. Stofflet. Stofflet later went on to found the newspaper “The Hamburg Item.”

Phoena lived until December of 1936. She is buried among the rest of her Guth family including Maria’s husband John at the Bunker Hill Cemetery in Weissport.

![]() |

Perhaps one of these men behind the counter of the c. 1910 Lehighton

picture is Howard Koch who listed his occupation as "watchmaker."

He was employed by his sister's husband Harry J. Dotter a jeweler and

clockmaker on South First St. Lehighton. |

Coincidentally, Howard Koch, the son of cigar maker I. S. Koch, lived for a time in the 1940s as a boarder with George and Marguerite Acker. A near life-long bachelor, he later married a woman named Myrtle a few short years before he died.

![]() |

The Fourth Street view of the Culton memorial

near sunset. Marguerite and George Acker's

names are listed on this side. |

Amid a spacious spread of green in the Lehighton Cemetery you will find the marker engraved “Culton.” It subtly lists only the most recent of the four names Maria collected in her lifetime.

She is buried with three others, her widowed daughter Belle Meredith, her granddaughter Marguerite and her husband George Acker.

None of Maria’s husbands are buried with her.

And I think Maria is quite ok with that. ![]() |

| The Maria Culton and Belle Meredith side of the Culton Memorial. Rest in peace Maria. |

%2BSmith%2Bshe%2Bwas%2Bone%2Bof%2B18%2Bfrom%2Btwo%2Bmothers%2Bsister%2Bto%2BMrs%2BWm%2BHadyt%2Bof%2BTowamensing%2BPvt%2BBenj%2BSearfoss%2Bcousin%2Bresz.jpg)

+wiki.jpg)